Is wool ethical? Well, to answer that, let’s dive into the environmental impacts of the wool industry and its effects on sheep (plus share some ace wool alternative fabrics too!)

A thick woollen jumper… a pair of hiking socks… winter gloves… it’s quite easy to look at them and assume that they’ve come from happy sheep grazing in rich pastures. However, the reality is often very, very different.

Wool is normally depicted as a by-product of sheep’s seasonal trim. Carefully taken from them to avoid their coats getting too big and heavy. But, behind the scenes, the wool industry can hold a much darker side of animal cruelty and harm to the environment.

As the public puts continuing pressure on brands for transparency, we’re getting more of an insight into the realities of the wool industry.

When the Pulse of the Industry Fashion Report, named wool as the fifth-worst product in terms of environmental harm, it caused big brand names like Boohoo to announce it would ban wool altogether (though they did end up reverting this decision…).

With wool often depicted as an ‘ethical’ material, with lots of outdoor uses, we thought we’d take a closer inspection. Keep reading to see just how the clothing industry affects our fluffy friends and the environmental impacts of wool that made us stop using it in the first place. Plus the awesome vegan wool alternatives available now.

Animal cruelty from wool

First off, where does wool come from?

There are quite a few different types of wool, and a lot of them come from different animals:

- Cashmere is taken from Cashmere goats

- Angora is taken from Angora rabbits

- Merino is taken from Merino sheep

- Lambswool is taken from lamb

Though there are lots of different wool types, most often, and particularly within the outdoor industry, it’s wool taken from sheep. Wool is often used for gloves and hats, and for thermal products or baselayers, Merino wool is also very common.

The wool industry paints an image of sheep producing unnatural amounts of wool and that shearing them is a necessity. Like a seasonal haircut before being sent bounding back into the fields. The stark reality is that sheep are beaten, mutilated and often killed in the shearing process.

Mulesing

Merino sheep are a popular breed of sheep, used for their wool as their skin contains folds. This means they produce more fur than other breeds. Their wool is often used in outdoor gear due to its warmth, wicking properties and because it’s lightweight.

These folds, particularly around their breed (their bums) and the tops of their legs, make them susceptible to flystrike. This is because these folds get moist with urine and faeces, creating the perfect breeding ground for fly larvae. This is flystrike, which if not treated can be fatal to sheep.

Framers carry out a process called mulesing on sheep, where crescent shape flaps of skin are removed for these susceptible areas. These scars are then less likely to breed flystrike. The whole process is often carried out without anaesthetic or painkillers on lambs who are only 2 – 10 weeks old.

This cruel process is not carried out for the sheep welfare but because dead sheep equates to a lower profit margin. As you can imagine it’s an incredibly painful procedure that leads to a lot of unnecessary suffering.

The cruelties of sheering within the wool industry

The process of shearing sheep can be also lead to injuries and death.

PETA sent undercover investigators into UK wool farms to get a better insight into the process. Their findings are horrifying as sheep are beaten, sometimes with their heads being stamped on.

Sheep often had gaping wounds as the result of shearing. This was either untreated or sewn up without sterilisation or painkillers. Some sheep who were so badly mutilated they couldn’t walk and were just left to die, without veterinary care.

Is this the case for all sheep farms?

As is the case with most things, as the scale of the business grows, profit becomes the key focus. This is where most of the suffering is seen as standards slip. More sheep cramped into smaller holdings and rushed through the shearing line as quickly as possible. Just seen as a commodity rather than a living animal.

Sheep will often have a better life on smaller farms, however, it’s almost impossible to avoid harm, pain and distress during the shearing process.

Do sheep need to be sheared?

Yes and no. Not the easy answer you were looking for…

It is argued that sheep need to be sheared to reduce the risk of infection from parasites and infections. It also helps to keep them cool in the summer months and avoid overheating.

On the other hand, it’s argued that sheep only produce the amount of wool they need to insulate themselves in the cooler months and shed it in the warmer months.

If left to their own devices, most sheep would shed their wool naturally as they did before we came along and started chopping it off for our socks. However, domesticated sheep have been selectively bred over hundreds of years to produce as much wool as possible. With some breeds, it’s now got to the point where they do need to be sheared.

As you can see, not a straightforward answer but let’s dig a little deeper.

If you want to fill your life with more ethical outdoor guides and inspiration, sign up for our newsletter to get our latest articles

Greenhouse gas emissions from wool farming

If there’s one thing we’ve learnt from our time living in the Yorkshire Dales in the UK, it’s that sheep eat a hell of a lot. In fact, that and pooping is pretty much all they do all day.

With all that munching, a lot of gasses build up in sheep intestines that have to escape. This causes them to fart, burp and poop (even more than J does) releasing methane into the atmosphere.

Methane is a greenhouse gas that causes a lot of harm when released into the atmosphere and is one of the leading contributors to climate change. Over 20 years, one kilogram of methane will warm the planet 80 times more than one kilogram of carbon dioxide.

Though it’s not as much as cows, one sheep produces around a whopping 30 litres of methane a day. In New Zealand, gasses from animals, which is mostly sheep, make up more than 50% of the nation’s total methane emissions. In the UK there are over 30 million sheep releasing methane into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change as they flatulate.

Water pollution caused by wool production

As well as releasing harmful methane into the atmosphere, all that pooping can be really harmful to waterways. The environmental impact of sheep farming has a lot to do with faecal matter which runs off into waterways, killing off wildlife and polluting natural water sources.

There are also huge amounts of chemicals used in wool farming and production. “Sheep dip” is a toxic chemical used on sheep to get rid of parasites. Disposing of it poses huge problems that can be extremely harmful.

A study in Scotland of 795 sheep dip facilities found that 40% presented pollution risks. It also found evidence of an incident that occurred in 1995, in which a cupful of sheep dip called pyrethroid cypermethrin killed 1,200 fish downstream from where it was dumped into a river. That’s a lot of destruction from a small amount of a very harmful chemical.

Whilst in Wales, sheep dip was named as the major cause of brown trout declines in the River Teifi. This had a hugely detrimental effect on biodiversity in the region.

Water pollution leads to “dead zones”

The issue of disposing of sheep dip and the run-off of chemicals from farming can pollute natural waterways. This can then lead to “dead zones” in natural bodies of water.

A dead zone is where excess nutrients and chemicals build up causing algae to grow at unnatural rates, sapping the oxygen from the water. This kills fish, plants and other animals and creates places like the dead zone off the Gulf of Mexico.

Water use for wool manufacturing

Water is not only needed to rear sheep, manufacturing wool also uses a lot of water.

One pound of wool uses 101 gallons of water.

Coupled with the water pollution caused by sheep farming, that’s a lot of water being used up. When you consider there are people in the world struggling to access clean water, it seems like a waste when it could be put to better use.

Wool farming and land use

In order to produce wool, huge areas of land are cleared worldwide for sheep to graze and to also grow their food. This has a hugely negative impact on the environment, resulting in deforestation, soil erosion and habitat loss. Particularly as wool uses more land than any other fibre.

Biodiversity loss

In England and Wales, farming has depleted uplands of wildlife such as eagles and mountain hares. After spending many years living in Yorkshire, it’s unbelievable just how much of the land is used for sheep farming and how little wildlife remains.

It’s not just in the UK that natural spaces are being gobbled up for farming. Rainforests are being felled at an alarming rate to make room for corn and soy plantations used to feed sheep. This leads to damaging biodiversity loss in these regions.

Soil errosion

With such a lot of land used for sheep farming or sheep feed, this causes harmful soil erosion. Animal agriculture ends up being one of the leading causes of soil erosion worldwide.

Land use

Huge amounts of land are needed to rear sheep and grow their food which depletes natural landscapes and wildlife.

Sustainble alternatives to wool

Amongst all the destruction of the wool industry, there is hope in the form of sustainable, vegan alternatives.

Recycled polyester or rPET

Ever wondered what happens when you put plastic bottles into the recycling bin? It may just end up being a coat or rucksack for your next trip. rPET is often used to make outdoor gear and equipment as it’s pretty sturdy.

Synthetic insulation

If you’re looking to stay warm and want outdoor products with thermal qualities, synthetic insulation is your answer.

This vegan down alternative is very similar to birds’ feathers, but stays insulated when wet and is cruelty-free. Plus, lots of research is being done to make synthetic insulation from 100% recycled materials.

Aren’t synthetics bad for the environment?

Although wool has its negative implications, synthetics do carry their own risks to their environment.

Synthetics are petrol-based, a non-renewable resource that can cause a lot of pollution in the mining process. Synthetics also take much longer to biodegrade and can cause microplastic pollution.

This isn’t the case for all synthetics, as recycled synthetics use materials that have already been mined. This makes use of products that would otherwise cause pollution in the ocean or in landfills. Lots of research is also being done into making synthetics more biodegradable too.

More resources to explore…

Is Leather Sustainable or Ethical?

Wool-Free Hiking and Running Socks for the Outdoors

Vegan Winter Layering Guide for Cold Weather

Vegan Hiking Boots and Buyers Guide

Linen

A bit of an unsung hero, linen is hypoallergenic, biodegradable and strong.

It can withstand high temperatures so is a popular choice for wading through jungles in the tropics. Linen manages to absorb moisture without holding bacteria and becomes stronger when it’s wet. It can absorb 20% of its weight in moisture before it feels damp. It even becomes stronger the more it’s washed, which is some pretty cool natural wizardry going on there.

Lyocell

Lyocell is considered environmentally friendly as it’s made from wood pulp in a closed-loop process.

It’s another hypoallergenic fabric that doesn’t cling making it wrinkle-free and soft. It’s 50% more absorbent than cotton which means it’s a popular choice for sports and outdoor wear.

Lyocell is sourced from the eucalyptus tree which grows quickly, without irrigation and very few pesticides. It can also be grown on land no longer fit for food due to soil erosion. The production of lyocell doesn’t use any toxic chemicals and 99.5% of the dissolving agent can be reused.

Compared to cotton it uses less than half as much water in production and less water throughout its life. Due to its good breathability, it doesn’t smell piffy as quickly as other fabrics. Avoiding the need to be washed as frequently.

Soy fabric

A by-product of soya bean processing, soya fabric has been nicknamed “vegetable cashmere”. Not the ideal choice for outdoor escapades, none the less it’s still a great alternative to wool.

It gained its nickname for its silky smooth touch, the durability of cotton and warmth that rivals wool-cashmere. Just a more sustainable option.

If you’re looking for vegan outdoor gear and wool alternatives all of our gear guides are animal-free

Organic cotton

When grown organically, cotton doesn’t use any harmful chemicals. It can be recycled and made into new clothes or yarn. It’s incredibly versatile, so can be used to make jeans, jumpers and hats. It also mixes well with other fabrics to make unique blends.

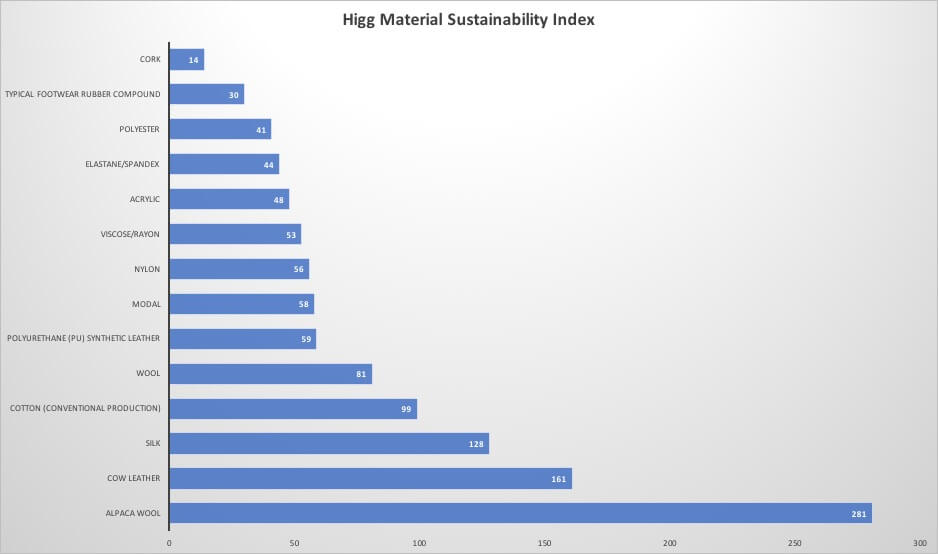

The carbon footprint of wool vs cotton is much higher as demonstrated by the Higg Materials Sustainability Index. Wool has a global score of 40.0 which is four times more than cotton at 8.8.

This is because of the growing process and because cotton uses a lot less water to produce than wool. It’s also easier to wash and faster to dry compared to wool.

Hemp

Hemp establishes itself well without the use of pesticides or chemicals and renews itself three times per year.

It’s great for soil as the plant’s roots protect the soil from run-off, whilst building up and preserving topsoil and subsoil structures.

It’s a natural and biodegradable fabric that is similar to linen in texture. It’s breathable and doesn’t trap heat, which can promote the growth of bacteria. And, it’s 10 times stronger than cotton.

Hopefully this article has shed a bit of light on the cruelties and environmental impacts of the wool industry.

The reasons listed are why we decided to stop using wool all those moons ago. Although wool is hailed for its wicking properties and being so lightweight. We felt the cons outweighed the pros. especially when you consider how cruel the industry is.

The aim of this article isn’t to urge you to throw out all your wool. Instead, to give an insight into the realities of the wool industry and what alternatives are available.

If you’re on the lookout for new gear but want to avoid wool our gear guides are a good place to start. Our guides are all vegan, so we never recommend wool and as always if you have any questions drop us a line and we’ll see how we can help.